A common misconception about Montessori education for the elementary-aged child is that there is a “free for all” atmosphere in which children have no structure or guidance and just do what they want all day. I recently came across this misconception when I was discussing such alternative education with a fellow parent. She noted that Montessori might be right for some kids — in particular, highly motivated self-starter types, but she worried that other children would fall through the cracks and just “sit around doing nothing.”

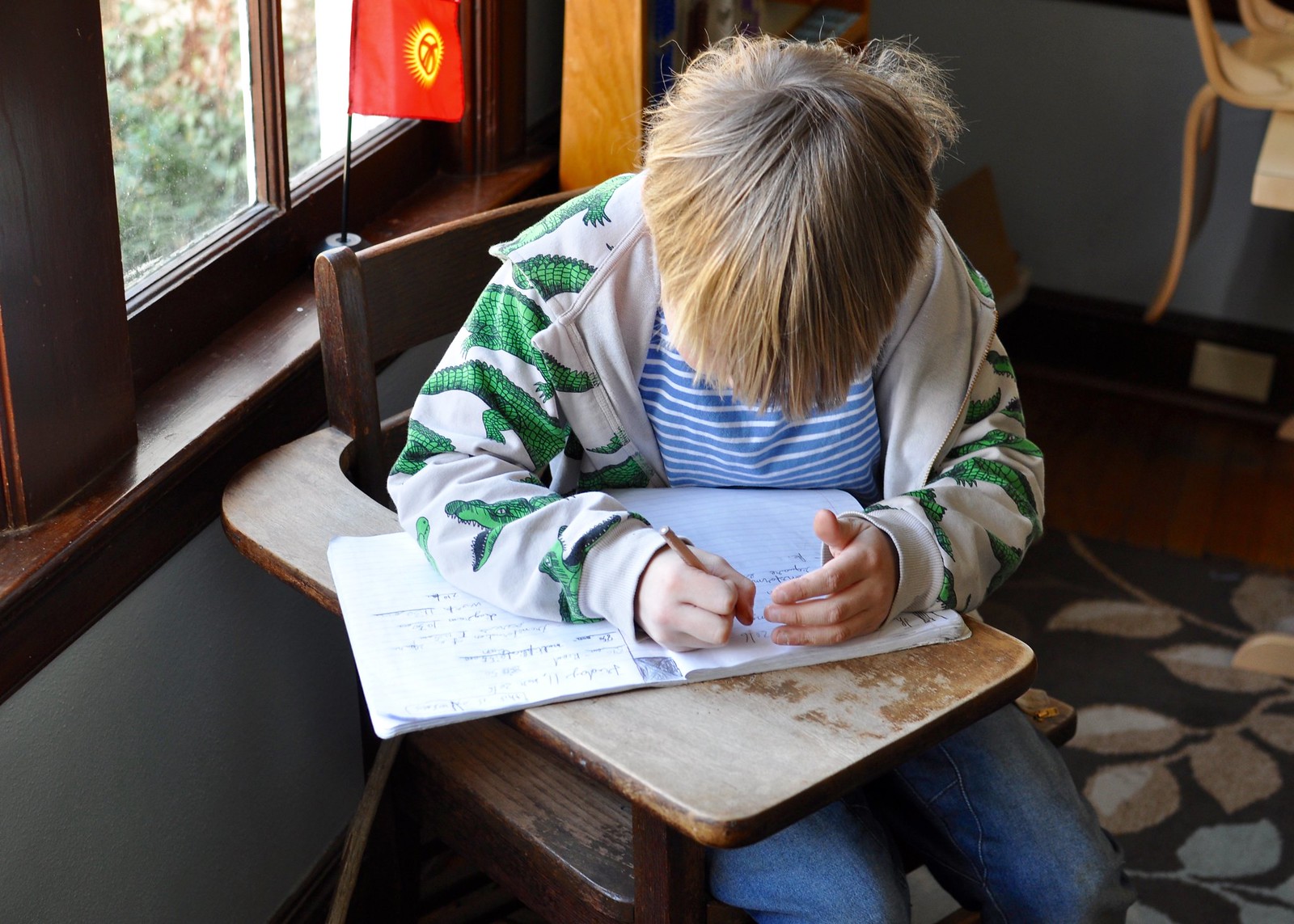

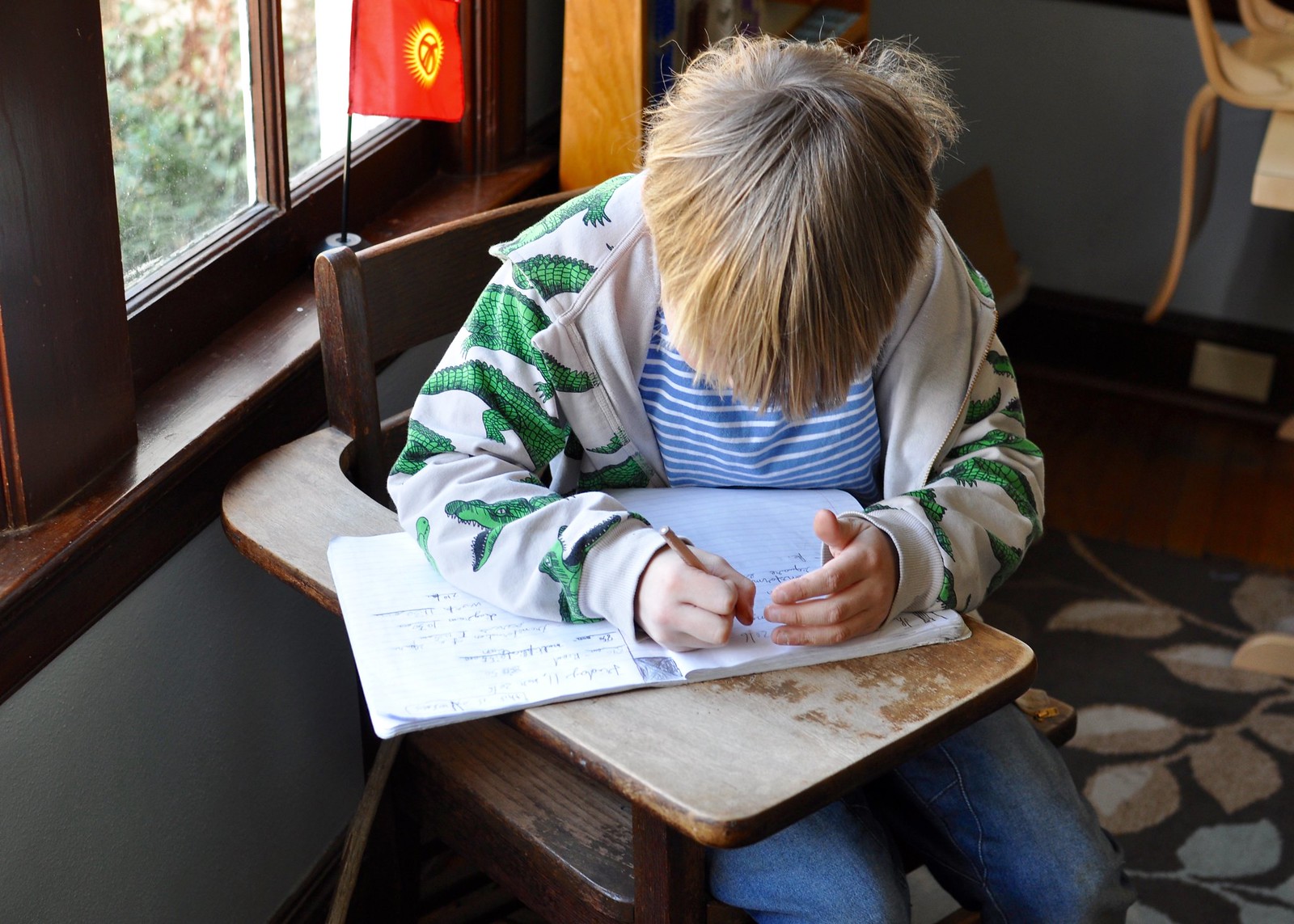

I found it interesting that this was anyone’s perception of a Montessori classroom, as what I have observed is quite the opposite; I have yet to see a child just sitting around doing nothing, and in fact, I am often quite impressed with the busy worker-bee mentality I see in the Montessori classroom. Children are working so intently, they often ignore the fact that there is even a parent in the same room, let alone one taking photos of them.

Sitting around doing nothing is not an option in a Montessori classroom. While the children have a wide range of work from which to choose, if a child is struggling to stay on task (I promise you, this is a rare occurrence), he or she receives redirection from the directress or guide. Again, most of the time this is not necessary, but there is not the “free for all” atmosphere some assume happens in a less structured school setting.

It is true that Montessori education is different when it comes to assessments. There are no tests, no grades, and there is no homework. However, that does not mean there is no assessment. Assessment is happening all the time in the Montessori elementary classroom, it just looks very different from the typical elementary school classroom.

Start with the set-up of the classroom. Students are placed in mixed-age classrooms, usually consisting of a three-year age block during which the same directress has the opportunity to work with each child. The importance of this cannot be overlooked; over the course of three years, a directress is able to understand each child as a whole child, as opposed to getting a glimpse of him or her before sending the child on to the next grade and teacher. Deeply knowing a child allows the directress not only to build a meaningful relationship with her, but also to introduce new concepts at developmentally appropriate times. Also, a three-year window gives a greater view of the “big picture” mentality of learning and development. It is easier to see progress, development, and potential for improvement in certain areas over the course of a longer period of time than a shorter one, especially since children develop at their own rates!

The mixed-age classroom also provides motivation and forward-thinking, which is a big part of its benefits. Younger children are motivated by the lessons and work they observe the older children engaging in; this is a natural trajectory of growth loaded with common sense. Often, younger children who have had a glimpse into the future (through watching an older student complete work they have not yet been exposed to) ask what they need to do to master and move forward to be ready for this future work. This brings up an integral piece of Montessori assessment: self-assessment.

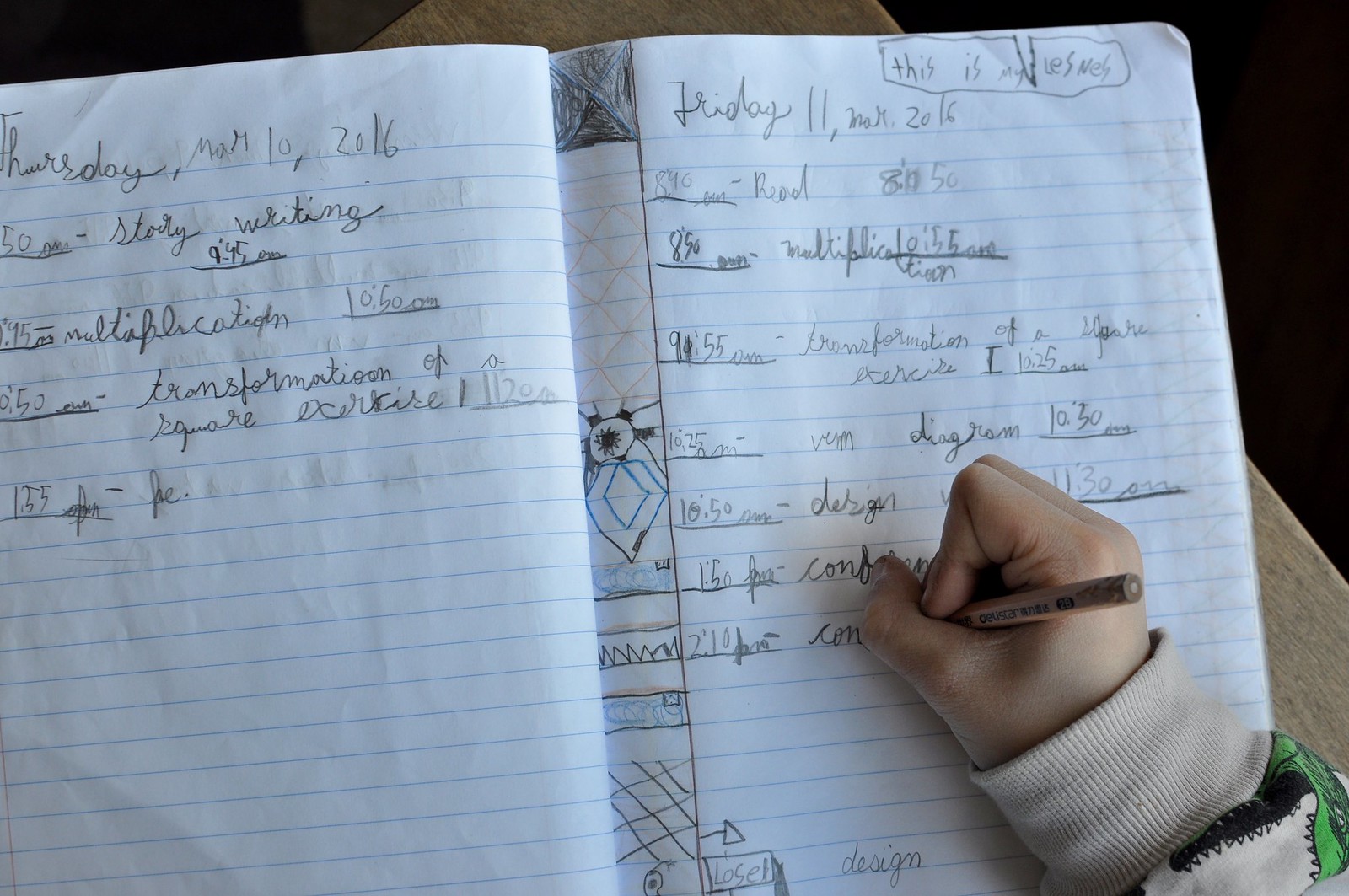

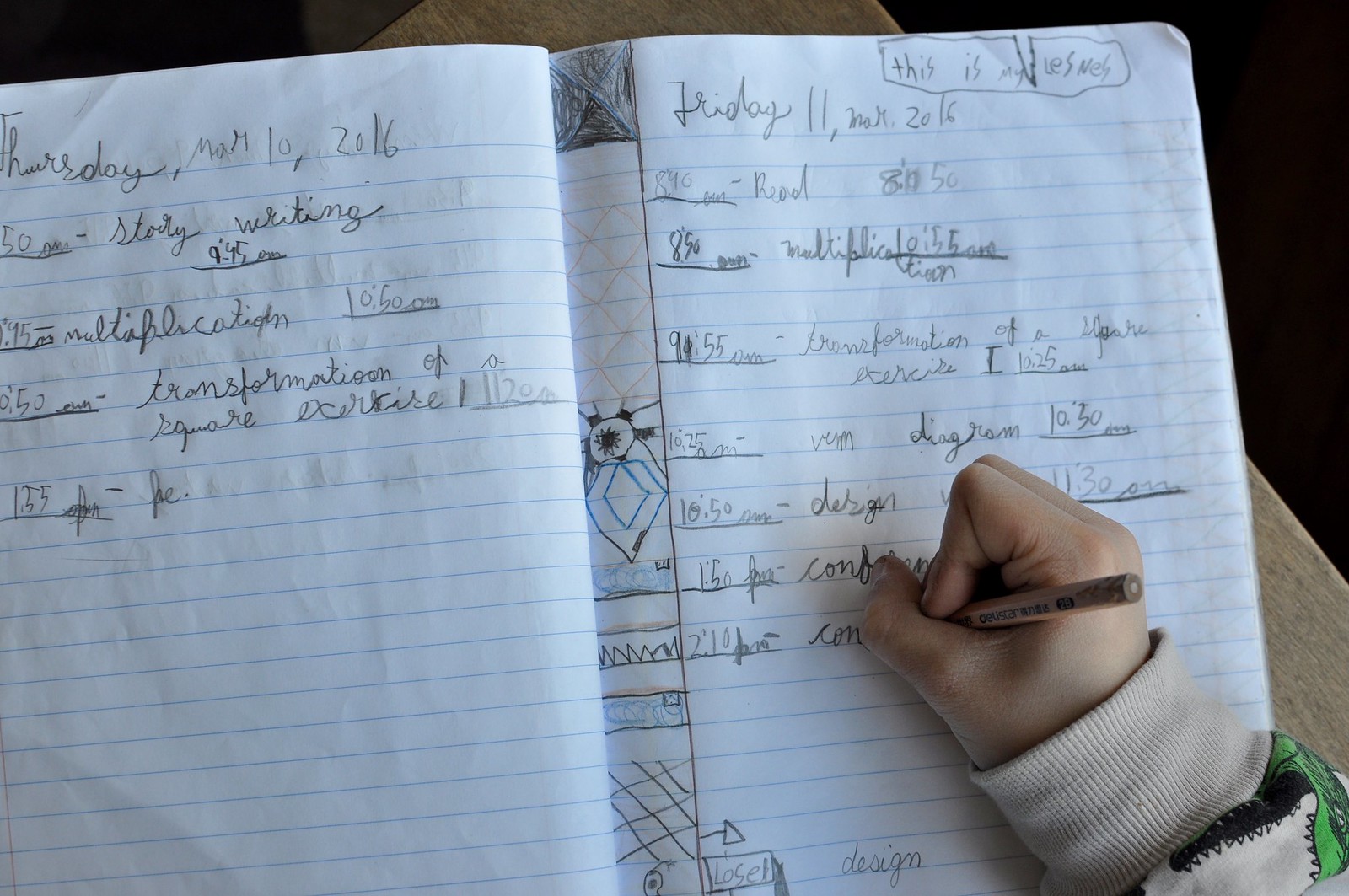

Self-assessment is a crucial piece of metacognition; it is an ability to observe, take a step back from one’s own work, recognize errors or areas for improvement, self-regulate, and ultimately self-correct. A huge part of the development of this skill is the maintenance of a journal. Each elementary student keeps a journal in which he writes down every lesson he receives and when he receives it, along with the work he does throughout the day. The journal is a valuable tool for accountability.

Above: A good example of a second year’s journal entry for a school day: 8:40 – 8:50am — Read, 8:50 – 9:50 – Multiplication, 9:55 – 10:25 — Transformation of a square exercise, 10:25 – 10:30 — Venn Diagram, 10:50 — 11:30 – Design work, 1:50 – 2:10pm – Conference (This particular day, Milo was obviously very focused on math! The next day will likely look very different)

Although Montessori guides and directresses do not give grades, they are constantly observing each child’s progress and readiness for new lessons. One assessment tool is simply trying the next lesson. Because each lesson builds on the previous one, if a child does not seem to understand the new lesson, the directress knows that she needs to go back, sit down with that child, and review the previous lesson. Every lesson is, therefore, an opportunity for assessment.

This is also the age during which perfection or mastery of work is of high significance. Children start to ask how to spell words, want to check their work to make sure it is correct, and adjust accordingly. They take pride in their work and correcting it is part of the learning process. Grades are not necessary or even helpful in this circumstance; it is the process of learning and the mastery of a lesson that is emphasized, as it is only through these means that a child may move on to the next (exciting!) lesson.

I also want to note the experience, high levels of education, and prestige of the AMI (Association Montessori Internationale) certified teachers (or directresses, as they are most often women). The training of a Montessori directress is intense and rigorous; these educators are deeply knowledgeable in child development, and each year of Montessori teacher training is equivalent to an additional year of graduate study. In addition, the Montessori directress has a special something that is hard to explain, but can best be described as a child-sense most of us do not have. There is, if I may add my opinion, a bit of magic involved in directing a Montessori classroom, and I find it fascinating and hugely special every time I observe.

Another method of assessment is the conference. This is not in reference to the parent-teacher conferences that happen twice a year (though those are very helpful for the parents); rather, this very important piece of Montessori education occurs one-on-one between the child and his directress every single week. Conferences are an opportunity for the directress to connect with each child, to looking through her journal, go through completed and incomplete work, and discuss what comes next. A conference often includes the directress asking, “What are you planning to work on next week?” combined with suggestions for what to work on based on the work provided and the observations of the directress throughout the week. The whole process includes making a plan, following through with the plan, and following up afterwards. Such meetings take a lot of practice, and within the actual conference are loads of opportunities for self-assessment, accountability, and self-reflection. The result is a higher-level learning strong in the critical thinking and self-regulation skills they will need as healthy, independent adults.

Ultimately, this is the goal: to raise self-aware, self-regulating, thoughtful human beings who are comfortable critically assessing their own work, as well as accepting criticism from others in a constructive, mature way. You’ll be hard pressed to find a test or grade that accurately reflects that!